Can Cotton Still be the “Fabric of our Lives”?

A Deep Dive into Cotton’s Complicated Past, Polyester’s Rise, and What Our Clothes Say About Us.

In a world growing increasingly weary of itchy polyester and synthetic materials, cotton and other natural fibers seem to be making a resurgence. While in between episodes of Love on the Spectrum, Netflix played a commercial for Cotton Incorporated. My first thought was, how is cotton something that can be advertised? And why are the ads targeting me? Cotton has been used to create everyday items for centuries. From clothing to bedding, towels, curtains, Q-Tips, the list goes on. In a world of advertising, was this cotton commercial attempting to influence me to buy products simply because they’re made of cotton?

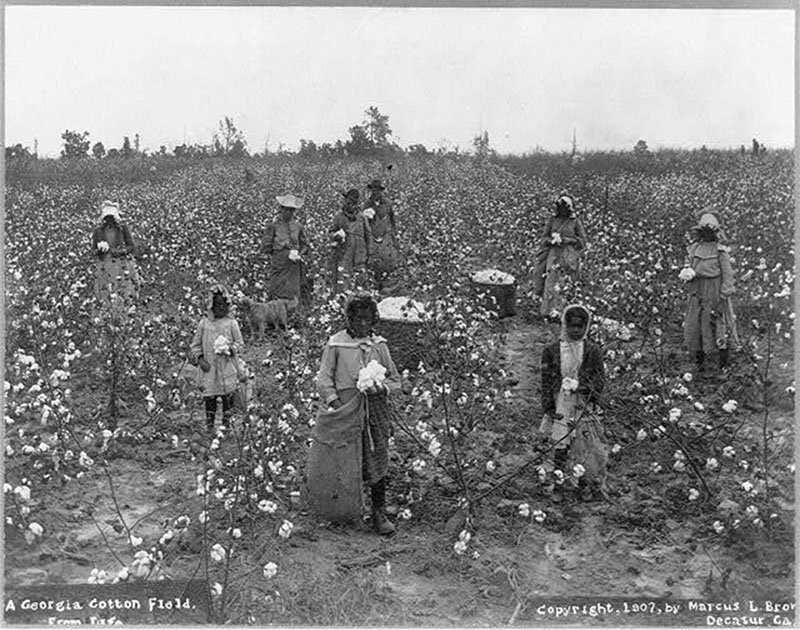

As a Black American, the thought of cotton strikes many emotions simultaneously. The obvious history surrounding the cultivation of one of the world’s most abundant natural fibers is rooted in racial trauma. Even with the abolition of slavery, Black people continued to be exploited through the application of sharecropping. I

n Ryan Coogler’s latest blockbuster hit, Sinners, we see cotton farmers, a hint at the lingering effects of American slavery.

So, how was cotton rebranded as “the fabric of our lives”? To answer this, we have to go back to the beginning.

There are several species of cotton, or Gossypium. Together, they account for roughly 80% of the world’s natural fiber production. Gossypium hirsutum is most commonly cultivated today. The species was popularized in the Western hemisphere, with origins tracing back to 5000 BCE in the Middle Nile Basin. A second species, Gossypium barbadense, has traditionally grown in the Americas, with evidence of its use appearing in 5800 BCE in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley. Pakistan’s Indus River Valley is formally recognized as the birthplace of spinning cotton into woven fabric.

With cotton evolving alongside humans, we learned to use the fiber to create clothing and other textiles. Peruvians would dye cotton to customize tunics as early as 750 CE. On the other side of the globe, dressmakers in China started to incorporate dyed fabrics. India’s longstanding history of growing and processing cotton influenced Britain to begin importing the fiber, allowing them to create their own print shops.

Like many things the British “discovered” the cotton supply chain soon fell to shit. When Columbus landed in the Bahamas in 1492, he was greeted by fields of growing cotton. Word eventually got back to Europe, and by 1556, the seeds were being planted in Florida. Over the coming century, America’s cotton production was booming. However, it was only successful due to the enslaved labor of early African Americans.

Cotton that was grown and harvested in the American colonies was shipped back to Britain, where it was converted into printed fabrics. As the colonies moved towards independence, they began processing their own cotton. A boom in mass production and processing speed enabled an overabundance of cotton.

Even after slavery was abolished, formerly enslaved people remained essential to cotton production. As sharecroppers, they paid rent by giving a portion of their crops to landowners, often leaving them with little to no profit. As a result, they rarely experienced the full benefits of their labor.

As cotton production evolved, so did the art of making clothes. From the cotton gin to the sewing machine, our need for convenience has moved us from making clothes with natural fibers to synthetic ones

The quality of clothing has traditionally been an indicator of status, a practice that extends to modern day. Historically, clothing was made by those who wore it, and specially made clothing was a luxury only afforded to the wealthy.

In the 19th century, things began to change. The rise of textile mills allowed for the creation of mass manufacturing. Examples of early mass-produced garments are undershirts and pantaloons.

As with any technology, making clothes became easier over time. Then, the invention of synthetic fibers allowed clothing to be made cheaper. In 1910, the American Viscose Company created rayon, a semi-synthetic fiber made from plant cellulose. However, two decades later, a different American company was about to change the projection of fashion and textiles.

DuPont, a chemical company, invented nylon, a fully synthetic fiber made from petroleum. Throughout the 20th century, other unnatural fibers went on the market, such as acrylic and polyester. By 1965, manufactured fibers accounted for 40% of the U.S. fiber market. Manufacturers worked hard to sway the public to adopt synthetic fabrics.

By 1951, the main selling point was that polyester clothing could be worn for 68 days and still appear “fresh”. Along with man-made fibers came the plastic boom. It was cheaper to produce than aluminum, more durable and predictable than glass. In terms of profitability, switching to plastic was a no-brainer to most companies.

These new fabrics were used to create anything from clothing to carpet. In fact, stockings and panties hose were soon converted from silk to nylon, saving loads of money in the process. However, the public began to approach these fibers with caution as synthetic carpets were known for their flammability.

Overtime, they were refined to be less flammable and safer from human use. But it was this synthetic spark that prompted cotton to fight for its spot as the world’s most abundant fiber.

In 1966, Congress passed the Cotton Research and Promotion Act, a direct response to a decline in the cotton market. A few years later, Cotton Incorporated was created. This non-profit organization’s focus is research and promotion, but it doesn’t actually produce any cotton products. One promotion tactic is advertising, and for advertisements to stick in the public’s mind, they need a catchphrase. Thus, the “Fabric of our Lives” was born.

Although cotton is heavily advertised, polyester remains the most widely produced fiber in the world. The fact is, polyester is significantly cheaper to manufacture, but this comes with detrimental side effects. Polyester contributes greatly to climate change as it’s made from fossil fuels and creates an abundance of CO2 to produce.

Plastic takes thousands of years to break down naturally, but plastic fibers are prone to pilling and fading. Technically, yes, they do last longer, but not in a good way. Synthetic fibers account for roughly 70% of clothing produced globally.

Not only did we start creating cheaper clothing, but we stopped producing it in the U.S. Now, almost every recognizable brand uses cheap labor, often in hazardous conditions, to produce cheap clothing that isn’t designed to last.

We make clothes more quickly, and abandon them just as swiftly. We donate clothes at such a high rate that we offload excess in the global south. When buying clothes, we should be analyzing their composition and longevity.

One thing to note is that cheaper manufacturing has heightened accessibility to fashion. Those who purchase fast fashion out of necessity should not be demonized, but those who profit off the oppression of garment workers should.

In conclusion…

Creating textiles with cotton is an ancient tradition. It is something that most civilizations share. It’s a way to show creativity, individuality, status, and culture.

As time progressed, colonizers used one of the world’s most abundant resources to oppress others. Processing cotton became easier, and making by-products allowed more people to profit and benefit. Then, one silly little company invented synthetic fibers, which in turn created a new system of oppression. Sweatshop workers in China, India, and Bangladesh make as little as $1.58 per hour, sometimes even less.

In a society filled with micro trends and temporary satisfaction, can we as consumers influence a clothing renaissance, or are we cursed to live a life fully controlled by plastic? Is it even possible to fully embrace cotton as the fabric of our lives once more?

Aside from the environmental argument, we deserve better clothing and textiles. Those who create our everyday products deserve a better quality of life and a livable wage. Period. Cotton cannot truly be the fabric of our lives unless corporations value lives over profit.